![]()

![]()

![]()

1, 2 Biserka Sedić

1, 3 Franjo Liška

1, 4 Jadranka Pavić

1 Boris Ilić

5 Slavica Liška

6 Ana Mutić

1 University of Applied Health Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia

2 Faculty of Dental Medicine and Health Osijek,

Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Osijek, Croatia

3 Alma Mater Europaea – ECM, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia

4 University of Rijeka, Faculty of Health Studies, Rijeka, Croatia

5 Clinic for Pulmonary Diseases, University Hospital Centre Zagreb, Croatia

6 Nursing School Vinogradska, Zagreb, Croatia

https://doi.org/10.24141/2/9/2/12

Author for correspondence:

Franjo Liška

University of Applied Health Sciences, Zagreb, Croatia E-mail: franjo.liska@hotmail.com

![]()

Keywords: dementia, older adults, elderly, exergaming, cognition

![]()

![]()

Introduction. As the world population is ageing, it is expected that the number of many chronic diseases common for elderly age will rise, including different forms of dementias. Dementias are a global problem, considering there are no effective medication or cure to date, and there is a need to develop new tools that would be used to slow down or postpone symptoms, of which one of the most pronounced is cognitive de- cline. The use of exergaming has been proved to im- prove cognitive functioning in healthy elderly people and in those suffering from various diseases.

Aim. The aim of this review was to present research on the impact of this intervention on the cognitive abilities of older adults suffering from dementia.

Methods. A literature search was conducted in Pub- Med and Scopus for articles published between 2015 and February 7, 2025. Predefined search strings and inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the PICO frame- work were applied to identify relevant studies.

Results. A total of 213 papers were identified through database search, using search strings. Fol- lowing duplicate removal and study selection, 8 stud- ies were included in this review.

Conclusion. Only a few randomized controlled stud- ies have been conducted researching into the effec- tiveness of exergaming on cognition in people with dementia. Findings indicate that exergaming may be a promising tool for improving cognition in this popu- lation, but more well-designed studies are needed to confirm its efficacy.

![]()

![]()

As the world population is ageing, the number of peo- ple suffering from major neurocognitive disorders, including different forms of dementias is expected to rise even more in the following years (1). Dementia is a syndrome characterized by progressive brain damage, affecting cognitive function and difficulty performing everyday activities. 60–70% of all dementia cases are Alzheimer’s disease, which is the most common form of the condition. According to World Health Organiza- tion (WHO) data from 2023, an estimated 55 million people worldwide are currently living with different forms of dementia, and projections from WHO Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017 – 2025, suggest that this number will nearly tri- ple by year 2050 to 132 million. These numbers have a great effect on healthcare systems and overall so- ciety, and there is a great need for action on a global plan (2,3). Regarding the European Union (EU) and according to data from Eurostat and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2018, the number of people with dementia was

9.1 million. Projections estimate that this number will

double by 2050, reaching 18.7 million (4). The most common dementias have no cure and there is no ef- fective disease-modifying medication, therefore one of the alternatives is definitely to develop and imple- ment non-pharmacological interventions (5). We now know that physical exercise has a positive effect on cognition in elderly people without dementia, and, the lack of physical activity during earlier life is a risk fac- tor for developing dementia. We are living in an era of rapid technological advancement and the rise of new interventions in healthcare and social care systems, and one of these new interventions is exergaming.

Studies in this field have already been conducted, and have shown that among healthy older adults and in patients with mild cognitive impairment, mul- tiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease, exergames compared to physical exercise training alone have a better effect in improving global cogni- tive function (6). Exergaming refers to playing vide- ogames that involve physical movement (7). To play these games users need to use various equipment like VR headsets, motion sensors, balance boards, control- lers etc. (8). At present, there is growing interest in researching the effects of exergaming on improving

cognitive functions in older adults with mild cogni- tive impairment and dementia. Various studies sug- gest that exergaming could have a positive impact on cognitive abilities but it is important to say that it is difficult to draw general conclusions because of the differences in study designs, intervention protocols, and participant characteristics (8,9). In order to pre- vent cognitive decline, physical exercise alone may be insufficient. Interventions which combine physical activity and cognitive stimulation seem to be more ef- fective in maintaining cognitive functions (10,11).

![]()

![]()

The aim of this literature review is to examine the effects of exergaming on cognitive functioning of el- derly people with dementia.

![]()

![]()

A search of the PubMed and Scopus databases was conducted on February 7, 2025, to identify studies relevant in the field of research on the effects of exer- gaming on cognition in older adults with dementia. The search was conducted using search strings combining terms related to dementia, aging, cognitive function, and exergaming, refined with Boolean operators (AND, OR), and limited to articles published between January 2015 and February 2025. The search targeted titles, abstracts, and keywords in the databases mentioned above. The full search strategies for each database, including the exact keyword combinations, are shown in Table 1. Search was conducted following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria as shown in Table 2, which were based on the PICO framework shown in Table 3. The target population included individuals aged 65 and older diagnosed with dementia, while the intervention of interest was exergaming. Exergaming is a relatively new intervention so both full-scale ran- domized controlled trials (RCTs), and pilot RCTs were included to have a more detailed review. Risk of bias was not assessed in this review, as it is a narrative re- view and focused on summarizing available evidence.

Table 1. Databases with search string and number of hits | ||

Core collection | PubMed | Scopus |

Search string | ((“dementia”[Title/Abstract] OR “Alzheimer Disease”[Title/ Abstract] OR “cognitive impairment”[Title/Abstract] OR “major neurocognitive disorder”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“older adult*”[Title/Abstract] OR “elder*”[Title/Abstract] OR “aged”[Title/Abstract] OR “senior*”[Title/Abstract] OR “geriatrics”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“cognition”[Title/ Abstract] OR “cognitive function”[Title/Abstract] OR “cognitive decline”[Title/Abstract] OR “cognitive performance”[Title/Abstract])) AND (“exergame*”[Title/ Abstract] OR “active video game*”[Title/Abstract] OR “interactive video game*”[Title/Abstract] OR “serious game*”[Title/Abstract]) | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“dementia” OR “Alzheimer Disease” OR “cognitive impairment” OR “major neurocognitive disorder”) AND (“older adult*” OR “elder*” OR “aged” OR “senior*” OR “geriatrics”) AND (“cognition” OR “cognitive function” OR “cognitive decline” OR “cognitive performance”) AND (“exergame*” OR “active video game*” OR “interactive video game*” OR “serious game*”)) |

Number of hits | 52 | 168 |

Table 2. Criteria for including and excluding results | ||

Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

Population | Adults ≥65 years diagnosed with dementia | Other |

Language | English | Other languages |

Text Availability | Full-text available | Abstract only, no full text |

Article Type | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), pilot RCTs | Other study designs |

Table 3. PICO Framework for study selection | |

Component | Description |

Population (P) | Older adults (≥65 years) diagnosed with dementia |

Intervention (I) | Exergaming interventions that incorporate physical activity as a core component (e.g., VR-based exercises, interactive motion-controlled games, active video games). |

Comparison (C) | Standard care (no intervention), conventional exercise programs, or other control conditions used in included RCTs. |

Outcome (O) | Cognitive function (e.g., memory, executive function, psychomotor speed, global cognition). |

![]()

![]()

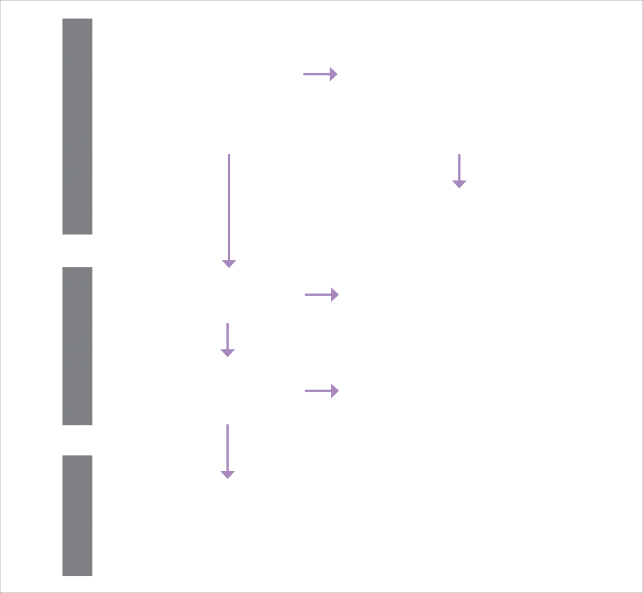

A total of 213 articles were obtained by searching both databases, of which 52 by searching the Pub- Med database and 161 by searching the Scopus database. The distribution of published articles by publication year is shown in Figure 1, showing the number of studies published by year prior to applying inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Fifty duplicate articles were removed using Zotero, resulting in 163 remaining articles. After screening

titles and abstracts following the inclusion and ex- clusion criteria listed in Table 2, 119 articles were excluded for not being RCTs, 33 for not meeting pop- ulation criteria, and 3 for not meeting the exergame intervention.

The process of the extraction of the final articles is shown in Figure 1, following the PRISMA flow dia- gram (12). After the final selection of studies, in this literature review we included 8 relevant articles that matched our predefined search strategy. An over- view of included articles by publication year is shown in Table 4. Most of the included studies reported

some cognitive benefits from exergaming, particu- larly improvements in psychomotor speed and global cognition, while effects on certain specific cognition domains such as memory were less consistent. Sev- eral studies also noted physical or mood benefits in the exergaming groups.

Regarding effects of exergaming on cognitive func- tions, five out of eight included studies have shown explicit benefits. One study showed improvements in psychomotor speed, though it did not show improve- ments in memory or executive processes, and two studies primarily investigated outcomes that were not related to cognition, such as neuropsychiatric symptoms.

![]()

![]()

Overall, the evidence from observed studies sug- gests thar exergaming has beneficial effects on cer- tain cognitive functions in older adults with demen- tia, along with improvements in related areas such as motor skills and even neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Regarding quality of life, majority of included studies that investigated this aspect, did not show signifi- cant improvements.

Wiloth et al. in their research concluded that exergam- ing can improve motor-cognitive functions in people with dementia. In their intervention group (IG), they used exergame system Physiomat that combines balance tasks with cognitive challenges. Their study showed positive impact in the duration and accuracy of task execution in the exergame IG compared to the control group (CG). After 3 months, a follow-up was conducted. The benefits diminished, but remained higher in the IG group. However, they point out sev- eral limitations, such as not having a non-intervention control group, a possible Hawthorne effect, and a short follow-up period (13). Werner et al. in their re- search also used Physiomat system to analyse the time course of improvement in motor-cognitive func- tions. Their research also showed positive effects of exergaming, which plateaued after the first 3 weeks of intervention. This could suggest that initial motor- cognitive improvements in exergame may be rapid, but for maintaining progress it may require a gradual increase in exercise difficulty. Best improvements were identified in participants with initially lower cognitive abilities. Regarding limitations, this study lacked a CG for comparison and had a relatively small

Figure 1. Distribution of published articles by publication year prior to applying inclusion and exclusion criteria

![]()

Included

Screening

Identification

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram

sample, which limits the applicability of the results to the wider population of people with dementia (14). Furthermore, two studies by Karssemeijer et al. con- ducted in 2019 were included. Both studies investi- gated the effects of Bike Labyrinth exergaming on physical and cognitive functions in people with de- mentia. This exergame combines cycling on a station- ary bike with a virtual surrounding where participants drive through cities while solving cognitive tasks, in- cluding response inhibition, switching between tasks, and speed of information processing. The first study

investigated the effects on frailty and showed that IG significantly reduced frailty compared to the CG although there was no improvement in motor skills, physical activity or activities of daily living. Second study examined the effects on cognitive functions and showed that IG group had improvements in psy- chomotor speed, and this effect was maintained after 24 weeks, compared to CG. However, there were no significant improvements in executive functions, epi- sodic memory, or working memory. Their results could be clinically important, as it is known that in patients

Table 4. An overview of articles by publication year identified in the literature review | ||||||

Authors | Methods | Intervention duration (IG and CG) | Purpose | General outcomes | Follow up | Limitations |

Wiloth et al. 2017 (13) | RCT (10 weeks, 99 participants, 2 groups: IG-exergame, CG-low intensity strength and flexibility while seated | 10 weeks, IG: 2x per week, 1.5h CG: 2x a week, 1 hour | To evaluate effects of Physiomat exergaming on motor-cognitive functions in older adults with dementia | Significant improvement in duration and accuracy of task execution in motor-cognitive functions, improvement in transfer also to untrained tasks | After 3 months, improvements in the IG group declined, but remained superior to those in the CG | No usual care group included, no long-term follow up |

Werner et al. 2018 (14) | Secondary analysis of RCT (10 weeks, 56 participants, IG group only) | IG: 10 weeks, 2x per week, 10 min | To analyse time course of motor-cognitive improvements and predictors of early training response | Significant improvements in exergame-based motor-cognitive performances within 3 weeks, benefits plateaued later, lower baseline cognitive ability predicted greater improvements | No follow up | No control group comparison, small sample size, focus on short-term improvements, limited generalization to severe dementia cases |

Karssemeijer et al. 2019 (15) | RCT (12 weeks, 3 groups 115 participants: IG -exergame, CG1-aerobic training, CG2-active control) | 12 weeks, 3x per week IG: Exergaming (30–50 min per session, cycling with cognitive tasks) CG1: Aerobic training (30–50 min per session, cycling without cognitive tasks) CG2: Active control (30 min per session, relaxation & flexibility exercises | To examine whether exergaming can reduce frailty in older adults with dementia | Exergaming reduced frailty compared to the control group. No major effects on physical function or daily activities | After 24 weeks | No blinding, only mobile participants included, some tests not feasible for all participants |

Karssemeijer et al. 2019 (16) | RCT (12 weeks, 3 groups, 115 participants: IG -exergame, CG1-aerobic training, CG2-active control) | 12 weeks, 3x per week IG: Exergaming (30–50 min per session, cycling with cognitive tasks) CG1: Aerobic training (30–50 min per session, cycling without cognitive tasks) CG2: Active control (30 min per session, relaxation & flexibility exercises) | To examine the effects of exergaming on executive functions in older adults with dementia | Both exergaming and aerobic training improved psychomotor speed compared to the active control group, with effects sustained at the 24-week follow- up. No significant improvements were observed in executive functions, episodic memory, or working memory | After 24 weeks | No blinding, only mobile participants included, short intervention period (12 weeks), cognitive improvements may require longer training duration, possible floor effect |

Table 4. An overview of articles by publication year identified in the literature review | ||||||

Authors | Methods | Intervention duration (IG and CG) | Purpose | General outcomes | Follow up | Limitations |

Robert et al. 2021 (17) | Cluster RCT (12 weeks, 125 participants, 2 groups: IG-exergame CG- standard care) | 12 weeks, 2x per week for 15 minutes IG: X-Torp exergame (combined motor and cognitive tasks) CG: standard care | To examine the efficacy of serious exergames in improving neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with neurocognitive disorders | X-Torp significantly improved apathy and prevented worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms, while symptoms worsened in the control group. There were no significant improvements in cognitive function | 24 weeks | Small sample size, heterogeneous participants, different levels of stimulation, possible medication effects |

Swinnen et al. 2021 (18) | Pilot RCT (8 weeks, 55 participants, 2 groups: IG – exergaming, CG – music intervention) | 8 weeks, IG 3 times a week, 15 min per session, CG: 3 times a week, 15 min per session | To examine the effects of exergaming on cognitive, motor and neuropsychiatric outcomes in people with dementia in long-term care | Improved gait speed, mobility, balance and cognitive function, reduced depressive symptoms, no significant effect on quality of life or ability to perform activities of daily living | No follow up | Small sample, only motived patients included, short intervention period, no evaluated standardized protocol, no active control group, no follow up |

Swinnen et al. 2023 (19) | Pilot RCT (12 weeks, 18 participants: IG- exergaming, CG-traditional exercise) | 12 weeks, 3 times a week for 30 min | To examine the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of the VITAAL exergame prototype in people with severe neurocognitive disorder | Exergame group had better results in cognitive and physical functions then CG. There were no significant differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms, depression and quality of life | No follow up | Small sample size, only volunteers included, no control in medication effects, potential social desirability bias, low adherence rate, no follow up |

Wu et al. 2023(20) | RCT (12 weeks, 2 groups, 52 participants initially, 24 completed: IG- exergaming, CG-cycling) | 12 weeks, IG: 3 times a week, initially 30 min, gradually increased to 50 min), CG cycling with increasing resistance | To examine the effects of exergaming on cognitive and physical functions in older adults with dementia | Exergaming improved executive function (shorter reaction times, increased neural activity in attention and working memory) and enhancement of lower body strength and cardiorespiratory endurance compared to CG | No follow up | Small sample size (24 participants), high dropout rate, no nonexercise CG, MMSE not measured post intervention |

with dementia, psychomotor speed is an important predictor of functional decline, and that effects of ex- ergaming on cognitive functioning should be further researched and studied. Authors point out that peo- ple with more severe forms of dementia will have a harder time achieving improvement in cognitive func- tion using exergaming, than people with milder forms or healthy older adults (15,16). These findings are consistent with previous research which also indicate greater benefits of exergaming in populations with milder cognitive impairment (13,14). Another includ- ed study is by Robert et al. that researched the effect of X-Torp exergame on neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with neurocognitive disorders. Their results showed a reduction in apathy in the IG, while symp- toms worsened in the CG. No significant improve- ment in cognitive functions was found (17), which distinguishes this study from some earlier research (13,14,15,16). The findings support the thesis that exergaming can have a broader therapeutic effect but point out that there is a need for additional research with larger samples (17). Furthermore, two included studies were authored by Swinnen et al. First study is from 2021, and second from 2023 and both exam- ined the effects of exergaming on cognitive and motor functions in people with dementia in long-term care facilities. It is important to highlight that different intervention systems and protocols were used. In a study from 2021, the IG used pressure-sensitive plat- form that detects steps in four directions called “Divi- dat Senso” stepping exergame. Games were designed to train selective attention, flexibility, postural control and visuospatial working memory, and the level of dif- ficulty was automatically adjusted to the participants capabilities. The results showed improvements in gait speed, balance, mobility and cognitive function with a reduction in depressive symptoms compared to CG that watched music videos. Regarding quality of life and activities of daily living there were no significant changes. In their second study in 2023, the IG group used the “VITAAL stepping exergame,” a system with wearable foot sensors that combined balance exercis- es and cognitive tasks. The results showed that the IG group maintained or improved MMSE score while the CG had a deterioration. Also, motor functions were stable in the exergaming group, while they sig- nificantly decreased in the control group. Together, these studies suggest that exergaming may play an important role in preserving cognitive and motor skills in people with dementia (18,19). Furthermore, in a re- cent study by Wu et al., the IG used a device called

ExerHeart in which players played interactive game called Alchemist’s Treasure. In order to progress in the game participants had to run, avoid obstacles and collect objects, thereby incorporating physical and cognitive stimulation at the same time. Their results showed that exergame is superior to exercise alone in improving reaction speed, attention and working memory. Also, they concluded that exergame had a significant effect on muscle mass increase, lower ex- tremity strength, and cardiovascular endurance. Re- garding limitations, there was a high dropout rate of participants and a small sample size (20). In general, the studies mentioned above show that the use of exergame could have a beneficial effect on the cogni- tive, motor and neuropsychiatric functions in people with dementia. Most improvements have been shown in psychomotor speed, balance, mobility and motiva- tion, while effects on executive function and memory are less consistent.

Similar conclusions have been described in previous systematic literature reviews, which highlighted the similar effects of exergaming on cognitive and mo- tor functions in people with dementia like the results from the studies above (21,22). This further con- firms the need for future work with larger and more diverse samples to better understand the cognitive impact of exergaming interventions.

The most obvious gap in this literature review is the small number of studies conducted in this field of re- search, particularly those conducted on people with serious cognitive impairment. Also, despite the fact that the majority of these studies have shown im- provements both in physical and cognitive functions, the long-term sustainability of these effects is still unclear due to the limited duration of the interven- tions. Most interventions lasted about 12 weeks, and there is a lack of follow up after the therapy ended. Also, it is important to know that the use of exergam- ing in treating people with dementia has many prac- tical challenges, particularly due to different degrees of cognitive impairment and the need for expert su- pervision. Some of the participants have had difficul- ties in accepting and using the technology needed for the application of exergames, which suggests that there is a need for additional adaptations to en- sure better compliance and easier wider application in everyday care. Also, there is a problem of a high rate of participant dropout, which also indicates the

![]()

above-mentioned challenges in implementing exer- gaming-based interventions. Finally, there is a lack of control groups, which makes it difficult to compare exergaming with other forms of therapy.

![]()

![]()

According to the data shown in the research included in this literature review, it was found that the use of exergames could be a potentially useful intervention that positively affects the cognitive and motor abili- ties of elderly people with dementia. Given that the ageing population, particularly those suffering from various forms of dementias, is expected to grow, this will pose challenges for socioeconomic systems glob- ally. There is a need to develop instruments that can slow down or delay the progression of the disease and exergaming has shown great potential to do so. Further studies should be conducted on larger num- ber of participants, including different groups of peo- ple with dementia (mobile, immobile, those housed in institutions and those living in their own homes, etc.) in order to better develop and adjust such technolo- gies. By putting this issue in the focus of research- ers, substantial progress could be achieved in a short period of time, and it is important to note that fur- ther research is certainly needed to identify the best ways to implement these new technologies as a tool for slowing down cognitive decline in patients with dementia. Also, it is worth noticing that all included studies were conducted in controlled settings, which limits the generalization of the findings to home use without supervision.

Conceptualization and methodology (BS, JP); Data curation and formal analysis (FL, SL, BI, AM,); Inves- tigation and project administration (BS, FL); Writing – original draft (BS, FL) and Review & editing (BI, JP, SL). All authors have approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Not applicable.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not- for-profit sectors.

![]()

![]()

Jin R, Pilozzi A, Huang X. Current Cognition Tests, Potential Virtual Reality Applications, and Serious Games in Cognitive Assessment and Non-Pharmaco- logical Therapy for Neurocognitive Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Oct 13;9(10):3287. https:// doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103287

World Health Organization. Dementia [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/ fact-sheets/detail/dementia Accessed: 11. 12. 2024.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025 [In- ternet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/ global-action-plan-on-the-public-health-response-to- dementia-2017---2025 Accessed: 11. 12. 2024.

Dementia prevention [Internet]. Knowledge for Po- licy. Available at: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa. eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/dementia- prevention_en. Accessed: 11. 12. 2024.

Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, et al. Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. The Lancet Neurology. 2016;15(5):455–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00062-4

Stanmore E, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, de Bruin ED, Firth J. The effect of active video games on cognitive functioning in clinical and non-clinical populations: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neu- rosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Jul;78:34-43. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.04.011

Oh Y, Yang S. Defining Exergames & Exergaming [In- ternet]. Available at: https://meaningfulplay.msu.edu/ proceedings2010/mp2010_paper_63.pdf Accessed:

12. 12. 2024.

Cai X, Xu L, Zhang H, Sun T, Yu J, Jia X, et al. The effects of exergames for cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systema-

tic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2024 Jul 16;15:1424390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fne- ur.2024.1424390

Peng Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Sha L, Dong J, et al. Virtual reality exergames for improving physical function, cognition and depression among older nur- sing home residents: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Geriatr Nurs. 2024 Feb;57:31-44. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.02.032

Law LL, Barnett F, Yau MK, Gray MA. Effects of combi- ned cognitive and exercise interventions on cognition in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:61–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.02.008

Rocha R, Fernandes SM, Santos IM. The importance of technology in the combined interventions of cogniti- ve stimulation and physical activity in cognitive func- tion in the elderly: A systematic review. Healthcare. 2023;11(17):2375. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthca- re11172375

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Wiloth S, Werner C, Lemke NC, Bauer J, Hauer K. Mo- tor-cognitive effects of a computerized game-based training method in people with dementia: a randomi- zed controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health. 2017 Jul 6;22(9):1130–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786

3.2017.1348472

Werner C, Rosner R, Wiloth S, Lemke NC, Bauer JM, Hauer K. Time course of changes in motor-cognitive exergame performances during task-specific training in patients with dementia: identification and predic- tors of early training response. Journal of NeuroEngi- neering and Rehabilitation. 2018 Nov 8;15(1):100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-018-0433-4

Karssemeijer EGA, Bossers WJR, Aaronson JA, Sanders LMJ, Kessels RPC, Olde Rikkert MGM. Exergaming as a physical exercise strategy reduces frailty in people with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019 Dec;20(12):1502-8.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jam- da.2019.06.026

Karssemeijer EGA, Aaronson JA, Bossers WJR, Don- ders R, Olde Rikkert MGM, Kessels RPC. The quest for synergy between physical exercise and cognitive stimulation via exergaming in people with dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2019 Jan 5;11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13195-018-0454-z

Robert P, Albrengues C, Fabre R, Derreumaux A, Pancrazi MP, Luporsi I, et al. Efficacy of serious exer- games in improving neuropsychiatric symptoms in neurocognitive disorders: results of the XźTORP cluster randomized trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2021 Jan;7(1):e12149. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12149

Swinnen N, Vandenbulcke M, de Bruin ED, Akkerman R, Stubbs B, Firth J, et al. The efficacy of exergaming in people with major neurocognitive disorder residing in long-term care facilities: a pilot randomized con- trolled trial. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2021 Mar 30;13(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-

021-00806-7

Swinnen N, de Bruin ED, Guimarães V, Dumoulin C, De Jong J, Akkerman R, et al. The feasibility of a step- ping exergame prototype for older adults with major neurocognitive disorder residing in a long-term care facility: a mixed methods pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2023 Feb 23;1–15. https://doi.org/10

.1080/09638288.2023.2182916

Wu S, Ji H, Won J, Jo EA, Kim YS, Park JJ. The effects of exergaming on executive and physical functions in ol- der adults with dementia: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Serious Games. 2023 Mar 7;11:e39993. https:// doi.org/10.2196/39993

Hung L, Park J, Levine H, Call D, Celeste D, Lacativa D, et al. Technology-based group exercise interventi- ons for people living with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2024 Jun 13;19(6):e0305266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0305266

Zhao Y, Feng H, Wu X, Du Y, Yang X, Hu M, et al. Effec- tiveness of exergaming in improving cognitive and physical function in people with mild cognitive im- pairment or dementia: systematic review. JMIR Se- rious Games. 2020 Jun 30;8(2):e16841. https://doi. org/10.2196/16841