![]()

![]()

![]()

1 Jasmina Pleho

2 Dženan Pleho

3 Anes Jogunčić

4 Kenan Pleho

2 Edna Supur

1 Altijana Dizdarević

5 Ruvejda Dizdarević

2 Lutvo Sporišević

1 Medical High School Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

2 Primary Health Care Center of Canton Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

3 Public Health Institute of Canton Sarajevo

4 Wiener Rotes Kreuz, Wien, Austria

5 Medical student at the Sarajevo Medical School - SSST, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

https://doi.org/10.24141/2/9/2/3

Author for correspondence:

Dženan Pleho

Primary Health Care Center of Canton Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

E-mail: dzenanpleho@hotmail.com

![]()

Keywords: adolescents, health risk, lifestyle, obesity, prevention, screening

![]()

![]()

Introduction. Obesity is a significant public health issue and a prevalent preventable nutritional disor- der. It can result from hereditary factors, prenatal conditions, environmental influences, metabolism, and lifestyle choices. This condition leads to an accu- mulation of adipose tissue and increased body mass.

Aim. This study aimed to identify participants’ life- style habits, determine their nutritional status, and assess potential predictors of obesity.

Methods. The cross-sectional study included 354 students from the Sarajevo High School of Medicine, of whom 236 (approximately 70%) were female. Par- ticipants were aged 14 to 18 years, with a mean age of 16.32 ± 1.74 years. The study involved collecting anthropometric data from physical education class records and administering a structured questionnaire (socio-demographic characteristics and assessment of life habits) designed for this study.

Results. It was found that approximately one quarter of the subjects were overweight/obese. Unhealthy eating habits were prevalent, with around 50% of re- spondents consuming fruits and vegetables every day, 80% consuming sugar-sweetened beverages, snacks and fast food. The Pearson correlation test and linear regression determined that inappropriate eating hab- its, lack of physical activity and pronounced sedentary habits significantly affect the occurrence of excessive body mass/obesity in the subjects.

Conclusion. Research shows many adolescents have unhealthy habits and obesity, which pose serious health risks. Early screening and prevention are crucial to reduce these risks and promote long-term health.

![]()

![]()

Adolescence is the period between childhood and adulthood characterized by significant physical, cog- nitive, hormonal, emotional, and social development. It typically spans ages 10 to 19; however, Kingorn

A. et al. (1) categorize adolescence into early (10–14 years), middle (15–19 years), and late adolescence (20–24 years), highlighting that this phase is subject to various epidemiological, social, and environmen- tal influences distinct from those of childhood and adulthood. Early adolescence is considered one of the healthiest life stages but also a critical time when risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, unprotected sexual activity) are often adopted and can persist into adulthood, impacting long-term health (2). Adolescence is a period marked by a higher prevalence of obesity, with estimates suggesting ap- proximately 80% of obese adolescents will remain so into adulthood (3). Obesity constitutes a major public health challenge, ranking as the fifth leading cause of death globally and the principal cause of chronic non- communicable diseases in adulthood (4). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 39 mil- lion children under five were overweight or obese in 2020, and over 18% of children and adolescents aged 5–19 were overweight or obese in 2016 (5). Between 1975 and 2016, the prevalence of overweight or obe- sity in the 5–19 age group increased approximately

4.5 times. In the United States, obesity rates have more than doubled in children and tripled in adoles- cents over the past three decades, with 2015-2016 data indicating an obesity prevalence of around 18% in children aged 6–11 and approximately 20% in ado- lescents aged 12–19 (6). Obesity is a multifactorial condition resulting from the interplay of genetic fac- tors, prenatal influences, metabolism, environmental conditions, socioeconomic status, and other variables. Prolonged energy imbalance leads to excess energy storage in the body, culminating in obesity (7, 8). Life- style changes over the past four decades, particularly unhealthy dietary patterns characterized by excessive consumption of processed foods, fast food, sweets, snacks, and insufficient intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seafood, have sig- nificantly contributed to the rising prevalence of obe- sity among children and adolescents worldwide. Other contributing factors include skipping meals (notably

breakfast), consuming large portions of unhealthy food outside the family home, limited family meals, high sugary drink consumption, inadequate physical activity, and prolonged sedentary behavior (8-11). Obesity is a chronic non-communicable disease that negatively impacts almost every organ system, neces- sitating early detection to prevent or mitigate associ- ated conditions. Common comorbidities in adolescents with obesity include high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, non-alco- holic fatty liver disease, pseudotumor cerebri, muscu- loskeletal disorders, social isolation, low self-esteem, anxiety, eating disorders, and adolescent depression (7-11). Obesity is linked to accelerated coronary ath- erosclerosis in adolescents and young adults, leading to premature cardiovascular disease (12). Adolescents with obesity exhibit carotid intima-media thickening and arterial stiffness, signifying early vascular dam- age (13). The notable prevalence of obesity, its persis- tence from adolescence to adulthood, and its associa- tion with comorbidities underscore the importance of obesity screening, balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, and reduced sedentary behavior. In treating obesity in adolescents (1217 years), lifestyle modi- fications should be complemented by medical inter- ventions, such as Liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 analog, and bariatric surgery in appropriate cases (14).

Obesity among adolescents is a global concern. The inclusion of various age groups, sample sizes, meas- urement accuracy, and criteria for assessing nutri- tional status (WHO 2007 criteria, CDC 2000 criteria, and Cole International Obesity Task Force criteria) all influence obesity distribution. Many countries utilize national reference values to determine obesity; in the absence of such values, WHO Growth reference data for ages 5–19 were employed.

![]()

![]()

This study aimed to identify participants’ lifestyle habits, determine their nutritional status, and assess potential predictors of obesity.

![]()

![]()

![]()

A cross-sectional study involved 354 students from the Sarajevo Medical High School, Bosnia and Herze- govina, aged 14-18 years, conducted from February 12 to June 10, 2019. The students attended high school from the first to the fourth year. First-grade students were under 15 years old, second-grade stu- dents were mostly 15 and 16 years old, third-grade students were 16 and 17 years old, while fourth-year students were 17 and 18 years old. Only healthy stu- dents were included in the study. The school’s man- agement approved the research (approval number: 02-1-120/19, dated January 29, 2019). Participants provided informed consent in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration and its 2002 and 2004 amendments.

The study involved administering a questionnaire and collecting anthropometric data. A structured questionnaire with 19 questions gathered demo- graphic details, information on acute/chronic ill- nesses, and lifestyle habits. The dietary habits sec- tion was based on “Quantitative models of foods and meals” by Senta A. et al. (15). Body weight and height were obtained from physical education class records.

The questionnaire evaluated lifestyle habits, includ- ing meal frequency, regular breakfast consumption, food intake, physical activity, and sedentary behav- iors. Adolescents were instructed on how to com- plete a questionnaire concerning the distribution of lifestyle habits. Multiple responses were offered, classified as follows: Regular dietary habits included five meals a day, daily breakfast, and daily consump- tion of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and whole grains. The frequency of food intake was measured on an ordinal scale with the following categories: Never, Rarely, Once per week, 2 to 3 times per week, and Every day. Limited consumption of fast food, sweets, snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages was also considered. Adequate physical activity was

defined as exercising for an hour or more, five times a week or more. Sedentary behavior included watch- ing TV, using computers, or playing video games for over two hours, five or more times a week. Body mass index (BMI) is used to assess nutritional sta- tus by dividing body weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m²). Participants’ BMI values were compared with WHO 2007 Growth reference standards for ages 5-19. According to WHO criteria, participants were classified as thin (BMI < +1SD and

> -2SD) or overweight (> +2SD) (16).

The data obtained from the research were analyzed using IBM SPSS v27.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), version 27.0. The data were presented in the form of frequencies and relative representation within the sample (%). Analysis between the examined groups was performed using the Chi-square test. The nor- mality of distribution for linear variables, including age and body mass index (BMI), was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. BMI exhibited a non- parametric distribution. Dietary habits, specifically the frequency of consumption of certain foods and the number of daily meals, were evaluated using an ordinal scale. Frequency was measured on a five-lev- el ordinal scale, ranging from “never” to “every day.” Based on WHO recommendations, the presence of healthy eating habits was assessed. Breakfast skip- ping was examined using a binary response format (Yes/No). Participants provided information regarding their physical activity over the past seven days, as well as sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching televi- sion, playing video games). These responses were subsequently classified as either present or absent. Number of meals had a range from 1 to 5 or more meals. The association of BMI values with dietary habits, number of meals, and regular consumption of certain foods was tested using Spearman’s correla- tion. The accepted level of significance was set at p<0.05.

![]()

![]()

The final analysis included 354 adolescents aged 14– 18 years (average age 16.32±1.74 years), Out of the total sample, 236 (66.7%) were female respondents, while 118 (33.3%) were male respondents. Average age of male respondents was 16.05±1.88 years, and average age of female respondents was 16.52±1.32 years, with female respondents beeing significantly older (t=2.800; p=0.005). The distribution of students by gender did not show a statistically significant differ- ence from the first to the fourth grade (x2=5.743, df= 3; p=0.125). Dietary habits are presented in table 1.

The table presents dietary habits based on the fre- quency of food consumption, where the classification of good or poor habits was determined by the author according to specific numerical criteria for each food item. Good dietary habits for a particular food were assigned based on higher consumption frequencies, while lower frequencies indicated poorer habits. Dairy products such as low-fat milk and yogurt were classified as part of good dietary habits, whereas processed cheese was associated with poorer eating patterns. Similarly, frequent consumption of fresh vegetables, fruits, and lean meats was considered a good dietary habit, while processed meats, canned foods, and margarine were categorized as poor die- tary choices. The classification aligns with WHO rec- ommendations, emphasizing the importance of con-

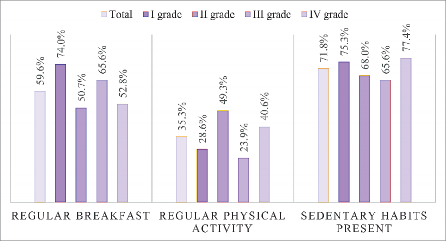

suming certain foods regularly to maintain a healthy diet. Approximately 50% of adolescents consume fruits and vegetables daily, while about 50% regu- larly eat fish and 40% regularly consume whole grain bread and cereals. Approximately 80% of respond- ents consume fast food and snacks daily, and 80% of adolescents drink sugar-sweetened beverages daily. About 70% of respondents consume sweets daily. Figure 1 shows analysis of regular physical activity, sedentary habits, and breakfast regularity.

The analysis showed that 59.6% of respondents regularly consumed breakfast, with the highest fre- quency in first grade (74.03%), decreasing in later grades (χ²=14.993, p=0.002). Regular physical activ- ity was reported by 35.31% of respondents, peak- ing in second grade (49.33%) and declining in other grades, with a significant difference (χ²=14.685, p=0.002). Sedentary habits were present in 71.75% of respondents, most notably in fourth grade, how- ever no significant age-related difference was found (χ²=4.428, p=0.212).

When compared with age of subjects, significant findings were observed only in regularity of break- fast (table 2).

Regular breakfast consumption was more common among younger participants, with a mean age of

16.9 ± 1.1 years, while those who did not regularly eat breakfast were significantly older, with a mean age of 17.2 ± 1.1 years (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in relation to physical activity or sedentary habits.

Figure 1. Percentage of students reporting regular breakfast, regular physical activity, and sedentary habit across grades

Table 1. Dietary habits | |||||||

Food Items | Every Day (A) | 2-3 Times per Week (B) | Once per Week (C) | Rarely (D) | Never (E) | Good Dietary Habits (N, %) | Poor Dietary Habits (N, %) |

Milk and Dairy Products | |||||||

Milk (0.5-2%) | 74 | 79 | 58 | 66 | 77 | 153 (43.22%) | 201 (56.78%) |

Milk (2.8%) | 76 | 85 | 70 | 73 | 53 | 196 (55.37%) | 161 (45.48%) |

Milk (3.2 or 3.5%) | 78 | 83 | 64 | 77 | 52 | 193 (54.52%) | 161 (45.48%) |

Yogurt, probiotic cultures, kefir | 100 | 76 | 71 | 65 | 42 | 176 (49.72%) | 178 (50.28%) |

Cheese: Fresh | 69 | 78 | 65 | 76 | 66 | 147 (41.53%) | 207 (58.47%) |

Processed | 63 | 82 | 83 | 73 | 53 | 209 (59.04%) | 145 (40.96%) |

Hard cheese | 52 | 66 | 94 | 81 | 61 | 236 (66.67%) | 118 (33.33%) |

Fats | |||||||

Sunflower oil | 141 | 86 | 48 | 44 | 35 | 127 (35.88%) | 227 (64.12%) |

Olive oil | 75 | 73 | 91 | 56 | 59 | 148 (41.81%) | 206 (58.19%) |

Butter | 72 | 107 | 90 | 52 | 34 | 179 (50.56%) | 175 (49.44%) |

Margarine | 43 | 61 | 72 | 97 | 81 | 250 (70.62%) | 104 (29.38%) |

Meat and Meat Products | |||||||

Beef | 55 | 78 | 93 | 67 | 61 | 226 (63.84%) | 128 (36.16%) |

Veal | 39 | 66 | 92 | 85 | 66 | 197 (55.65%) | 157 (44.35%) |

Lamb | 47 | 65 | 94 | 99 | 49 | 206 (58.19%) | 148 (41.81%) |

Chicken | 90 | 116 | 70 | 36 | 42 | 276 (77.97%) | 78 (22.03%) |

Turkey | 53 | 63 | 66 | 96 | 76 | 182 (51.41%) | 172 (48.59%) |

Processed meats (sausages, salami) | 107 | 95 | 67 | 48 | 37 | 85 (24.01%) | 269 (75.99%) |

Eggs | 105 | 99 | 68 | 54 | 28 | 199 (56.21%) | 155 (43.79%) |

Fish and Seafood | |||||||

Freshwater fish | 53 | 52 | 94 | 96 | 50 | 199 (56.21%) | 155 (43.79%) |

Saltwater fish | 45 | 66 | 81 | 91 | 71 | 192 (54.24%) | 162 (45.76%) |

Canned fish, pâtés | 72 | 79 | 88 | 66 | 49 | 115 (32.49%) | 239 (67.51%) |

Vegetables | |||||||

Leafy greens (spinach, kale, lettuce) | 62 | 84 | 82 | 76 | 49 | 146 (41.24%) | 208 (58.76%) |

Root vegetables (carrots, beets) | 61 | 86 | 97 | 68 | 42 | 147 (41.53%) | 207 (58.47%) |

Onions | 39 | 67 | 76 | 105 | 67 | 182 (51.41%) | 172 (48.59%) |

Tomatoes, eggplants | 61 | 96 | 71 | 76 | 50 | 157 (44.35%) | 197 (55.65%) |

Legumes (beans, peas) | 110 | 69 | 95 | 45 | 35 | 179 (50.56%) | 175 (49.44%) |

Fruits | |||||||

Fresh fruit | 81 | 113 | 77 | 40 | 43 | 194 (54.8%) | 160 (45.2%) |

Citrus fruits | 61 | 103 | 106 | 53 | 31 | 164 (46.33%) | 190 (53.67%) |

Nuts | 43 | 82 | 103 | 87 | 39 | 125 (35.31%) | 229 (64.69%) |

Dried fruits | 52 | 69 | 76 | 87 | 70 | 145 (40.96%) | 209 (59.04%) |

Jams, marmalades | 81 | 68 | 83 | 75 | 38 | 151 (42.66%) | 203 (57.34%) |

Table 2. Breakfast eating, regular physical activity and presence of sedentary habits regarding age of subjects | |||||

Age | |||||

Mean | SD | t | p | ||

Regular breakfast | Yes | 16.9 | 1.1 | 6.34 | <0.001 |

No | 17.16 | 1.08 | |||

Regular physical activity | Yes | 17.04 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.089 |

No | 16.98 | 1.12 | |||

Presence of sedentary habits | Yes | 17.01 | 1.15 | 0.33 | 0.743 |

No | 16.79 | 1.04 | |||

Table 3. Correlation between unhealthy lifestyle factors and body mass index | ||

Variables | BMI | |

Number of meals per day | Rho | 0.507 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of fruits | Rho | -0.627 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of vegetables | Rho | -0.560 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of snacks | Rho | 0.861 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of fast food | Rho | 0.779 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of sweets | Rho | 0.800 |

p | <0.001 | |

Consumption of sugar- sweetened beverages | Rho | 0.537 |

p | <0.001 | |

Lack of physical activity | rpb | 0.598 |

p | <0.001 | |

Sedentary habits | rpb | 0.759 |

p | <0.001 | |

Irregular breakfast consumption | rpb | 0.752 |

p | <0.001 | |

The values represent Spearman’s correlation coefficient, sig. - significance, probability | ||

in 24.7% of first-grade students, 8.11% of second- grade students, 12.5% of third-grade students, and 8.41% of fourth-grade students. Only one or two me- als per day had in total 14.4% of subjects, or regar- ding grades, 5.2% in first grade, 21.6% in second gra- de, 11.5% in third grade and 18.7% in fourth grade.

It was found BMI is significantly associated with poor dietary habits, physical inactivity and sedentary hab- its (Table 3). Consumption of snacks such as chips and sweets showed a very strong positive associa- tion with BMI. Higher consumption was correlated with higher values of BMI. Expressed sedentary hab- its, fast food consumption, irregular breakfast habits have strong influences on BMI. In addition, also lower and irregular consumption of fruits and vegetables emerged as predictors of obesity.

BMI - body mass index. Using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, no significant correlation was found be- tween age and BMI (rho=0.241; p=0.346). More fre- quent consumption of snacks, fast food, sweets, and sugar sweetened beverages was in correlation with higher values of BMI.

![]()

The majority of respondents reported consuming three daily meals, with prevalence rates of 42.9% among first-grade students, 41.89% among second- grade students, 46.88% among third-grade students, and 51.4% among fourth-grade students. The re- commended intake of five daily meals was observed

![]()

Our research indicates that approximately one-third of adolescents have excess body weight or obesity. Unhealthy lifestyle habits are linked to this condition: only 6% of 15-16-year-olds and 19% of 14-15-year- olds eat five meals a day, one-third to one-half skip

breakfast, about 50% do not consume fruits and vegetables daily, around 80% frequently eat fast food, snacks, sweets, and sugar-sweetened bever- ages, approximately 35% regularly exercise, and ap- proximately 70% are sedentary. Overweight/obesity rates in adolescents are in line with other studies. The CDC states that one in five U.S. children and ado- lescents is overweight/obese (17). In Ireland, 24% of adolescents were overweight/obese in 2020, up from 18% in 2006 (18). In Poland, 13-18-year-olds have a significant prevalence of overweight/obe- sity, with 15-19% of boys and 10-13% of girls af- fected (19). A cross-sectional study by Matana and Krajinović (2024) of 344 Croatian adolescents aged 15-18 found that 15% were overweight, with 11% overweight and 4% obese. These findings highlight obesity as a global health issue, suggesting the need for further cohort studies to identify specific factors influencing obesity prevalence.

We found that factors such as, number of meals per day, skipping breakfast, intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, snacks, and sweets, physical inactivity, and sedentary behavior, as well as lower intake of fruits and vegetables are significant indicators of ex- cess body weight/obesity in our respondents.

About 80% of our respondents do not eat the recom- mended five daily meals. Toschke AM et al. show that obesity rates drop with more daily meals: the odds ratio (OR) for obesity is 0.71 with 4 meals, and 0.57 with 5 or more meals compared to 3 or fewer meals

(21). The recommended five meals significantly low- er the risk of obesity in 16-year-old boys and girls: OR for overweight/obesity is 0.47 for boys and 0.57 for girls; for abdominal obesity, it is 0.32 for boys and

0.54 for girls (22). Our study did not find that more frequent meals reduce obesity. This may be due to differences in methodology, such as study type, par- ticipant number, follow-up period, criteria for defin- ing obesity and meal frequency, types and quality of meals, and potential errors in self-assessment. Demographic differences and individual variations among respondents also play a role.

Numerous studies have indicated that skipping breakfast affects nutritional status. It was found that a significant number of adolescents skip breakfast, which is a predictor of overweight/obesity. Chen S. et al. reported that in respondents aged 8-17 years, the odds ratio for overweight or obesity among those who skipped breakfast was 1.25 (23). Studies have shown that skipping breakfast increases the

risk of obesity by around 40% in children and ado- lescents (24). Unhealthy eating habits, such as high consumption of fats, sugars, and salt, along with low intake of fiber, fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seafood, contribute to obesity and related diseases. Approximately half of our respond- ents rarely eat fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while approximately 75% excessively consume pro- cessed foods, fast food, snacks, sweets, and sugar- sweetened beverages. Consuming fatty cheese, processed foods, fast food, refined grains, snacks, biscuits, high-fat milk, and sugar-sweetened bever- ages also increases the risk of excess body weight.

Liberali R. et al. state that eating fatty cheese, pro- cessed foods, fast food, refined grains, snacks, bis- cuits, and drinking high-fat milk and non-alcoholic beverages increase the risk of excess body weight (25).

Daily consumption of fruits and vegetables is part of a healthy diet. A study with 203 obese children aged 12-18 years showed that eating more fruits and veg- etables reduces obesity risk (26). However, our study did not find this link. This discrepancy might be due to different study methods, sample sizes, definitions of obesity, ways of measuring consumption, the qual- ity and quantity of fruits and vegetables consumed, high intake of processed foods and sugars, as well as demographic differences and individual variations.

Long-term consumption of sugar-sweetened bever- ages leads to obesity and related diseases. Our re- search indicates that adolescents consume sugar- sweetened beverages in large quantities, which may contribute to obesity. The European Society for Pae- diatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) links sugar-sweetened beverages with obesity and cardiometabolic diseases. They recom- mend that children aged ≥2 to 18 years limit sugar intake to less than 5% of their energy intake and drink water or unsweetened milk instead (27).

An examination of physical activity levels and sed- entary behaviors indicates that approximately two- thirds of adolescents are physically inactive, while around three-quarters engage in sedentary behav- iors. These patterns are frequently linked to un- healthy dietary practices, which serve as a risk factor for obesity and related comorbidities. Globally, it is estimated that approximately 80% of adolescents are insufficiently physically active and engage insed- entary behaviors (28). Previous research has empha-

sized the connection between these risk factors and obesity.

Public media can influence adolescent habits by ad- vertising unhealthy foods and beverages. The cur- ricula at the Sarajevo High School of Medicine, as well as in other high schools, could be designed to enhance the knowledge and skills of both teachers and students regarding healthy lifestyle habits in line with relevant recommendations.

In general there is a significant influence of public media on adolescent habits as they advertise un- healthy foods and beverages. Obesity is linked to other health risk factors. It is important to have a healthy dietary pattern and regular physical activity from an early age, as unhealthy habits can become difficult to change later. Both family practices and school activities contribute to promoting and main- taining healthy lifestyle habits.

The study’s limitations include focusing on only one high school, Sarajevo High School of Medicine. The questionnaire should be expanded to include food intake quantity and subsequently validated. Objec- tivity requires trained personnel using validated equipment to measure anthropometric parameters. Assessing hip circumference, waist-to-height ratio, blood pressure, blood glucose, lipid profile, sleep quality and duration would provide a more compre- hensive evaluation of health risks in adolescents.

Obesity poses serious health risks, necessitating focused efforts on lifestyle screening and obesity prevention in adolescents. Health education and pro- motion should play a greater role in school curricula, which is what we investigated.

![]()

![]()

This study found that approximately one-third of ad- olescents are overweight or obese, with higher BMI strongly associated with poor dietary habits such as irregular breakfasts, low fruit and vegetable intake, and frequent consumption of snacks, sweets, and fast food. The number of meals per day decreased with age, and most students did not meet the rec- ommended five daily meals, while physical inactiv- ity and high levels of sedentary behavior further contributed to excess body weight. These findings emphasize the urgent need for comprehensive strat- egies to promote healthier eating habits, encourage regular physical activity, and reduce sedentary life- styles among adolescents.

Conceptualization and methodology (LS, AJ, JP, DzP); Data curation and formal analysis (AJ); Investigation and project administration (JP,KP, AD, RD); Writing – original draft (LS, AJ, ES, JP, DzP) and Review & editing (LS, AJ). All authors have approved the final manu- script.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the participants.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not- for-profit sectors.

![]()

![]()

Kinghorn A, Shanaube K, Toska E, Cluver L, Bekker LG. Defining adolescence: priorities from a global health per- spective. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(5):e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30096-8

Blum RW, Mmari K, Moreau C. It begins at 10: how gender expectations shape early adolescence around the world. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(4 Suppl):S3-S4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.009

Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predic- ting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95-

107. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12334

Safaei M, Sundararajan EA, Driss M, Boulila W, Shapi’i A. A systematic literature review on obesity: Understan- ding the causes & consequences of obesity and re- viewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity. Comput Biol Med. 2021;136:104754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104754

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2024. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/de- tail/obesity-and-overweight.

Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Qi X, Locke J, Rehman S. Childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: a public health con- cern. Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19891305. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X19891305

Kansra AR, Lakkunarajah S, Jay MS. Childhood and adoles- cent obesity: a review. Front Pediatr. 2021;8:581461. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.581461

Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: from epi- demiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical asse- ssment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):251-

65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.017

Lister NB, Baur LA, Felix JF, Hill AJ, Marcus C, Rei- nehr T, et al. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41572-023-00435-4

Ryoo E. Adolescent nutrition: what do pediatricians do? Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54(7):287-91. https://doi. org/10.3345/kjp.2011.54.7.287

Klein DH, Mohamoud I, Olanisa OO, Parab P, Chaudhary P, Mukhtar S, et al. Impact of school-based interventi- ons on pediatric obesity: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43153. https://doi.org/10.7759/cure- us.43153

McGill HC Jr, McMahan CA, Herderick EE, Zieske AW, Malcom GT, Tracy RE, et al. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) Research Group. Obe- sity accelerates the progression of coronary atheroscle- rosis in young men. Circulation. 2002;105(23):2712-8 https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000018121.67607.ce

Mihuta MS, Paul C, Borlea A, Roi CM, Velea-Barta O-A, Mozos I, et al. Unveiling the silent danger of childhood obesity: non-invasive biomarkers such as carotid inti- ma-media thickness, arterial stiffness surrogate mar- kers, and blood pressure are useful in detecting early vascular alterations in obese children. Biomedicines. 2023; 11(7):1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedi- cines11071841

Nicolucci A, Maffeis C. The adolescent with obe- sity: what perspectives for treatment? Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-

01205-w

Senta A, Pucarin-Cvetković J, Doko Jelinić J. Quanti- tative models of food and meals. Zagreb: Medicinska naklada; 2004.

World Health Organization. Growth Reference Data for 5–19 years [Internet]. World Health Organizati- on; 2007. Available at: https://www.who.int/tools/ growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childho- od Overweight & Obesity [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2024. Available at: https://www. cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity- facts.html

Moore Heslin A, O’Donnell A, Kehoe L, Walton J, Flynn A, Kearney J, et al. Adolescent overweight and obesity in Ire- land-Trends and sociodemographic associations betwe- en 1990 and 2020. Pediatr Obes. 2023;18(2):e12988. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12988

Kułaga Z, Grajda A, Gurzkowska B, Wojtyło MA, Góźdź M, Litwin MS. The prevalence of overweight and obe- sity among Polish school-aged children and adoles- cents. Przegl Epidemiol. 2016;70(4):641-51.

Matana A, Krajinović H. Prevalence of overweight and obe- sity and association with risk factors in secondary school children in Croatia. Children (Basel). 2024;11(12):1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121464

Toschke AM, Thorsteinsdottir KH, von Kries R; GME Stu- dy Group. Meal frequency, breakfast consumption and childhood obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;4(4):242-

8. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477160902763341

Jääskeläinen A, Schwab U, Kolehmainen M, Pirkola J, Järvelin MR, Laitinen J. Associations of meal frequency and breakfast with obesity and metabolic syndrome traits in adolescents of Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(10):1002-

9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2012.07.006

Chen S, Zhang X, Du W, Fan L, Zhang F. Associati- on of insufficient sleep and skipping breakfast with overweight/obesity in children and adolescents: Fin- dings from a cross-sectional provincial surveillance project in Jiangsu. Pediatr Obes. 2022;17(11):e12950. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12950

Ardeshirlarijani E, Namazi N, Jabbari M, Zeinali M, Gerami H, Jalili RB, et al. The link between breakfast skipping and overweigh/obesity in children and ado-

lescents: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;18(2):657-64. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40200-019-00446-7

Liberali R, Kupek E, Assis MAA. Dietary patterns and childhood obesity risk: a systematic review. Child Obes. 2020;16(2):70-85. https://doi.org/10.1089/ chi.2019.0059

Tirani SA, Mirzaei S, Asadi A, Asjodi F, Iravani O, Akhlag- hi M, et al. Associations of fruit and vegetable intake with metabolic health status in overweight and obese youth. Ann Nutr Metab. 2023;79(4):361-71. https:// doi.org/10.1159/000533343

Fidler Mis N, Braegger C, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Do- mellöf M, Embleton ND, et al. ESPGHAN committee on nutrition: Sugar in infants, children and adoles- cents: a position paper of the european society for paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutri- tion committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(6):681-96. https://doi.org/10.1097/ MPG.0000000000001733

van Sluijs EMF, Ekelund U, Crochemore-Silva I, Guthold R, Ha A, Lubans D, et al. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):429-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01259-9